(much more to be added yet)

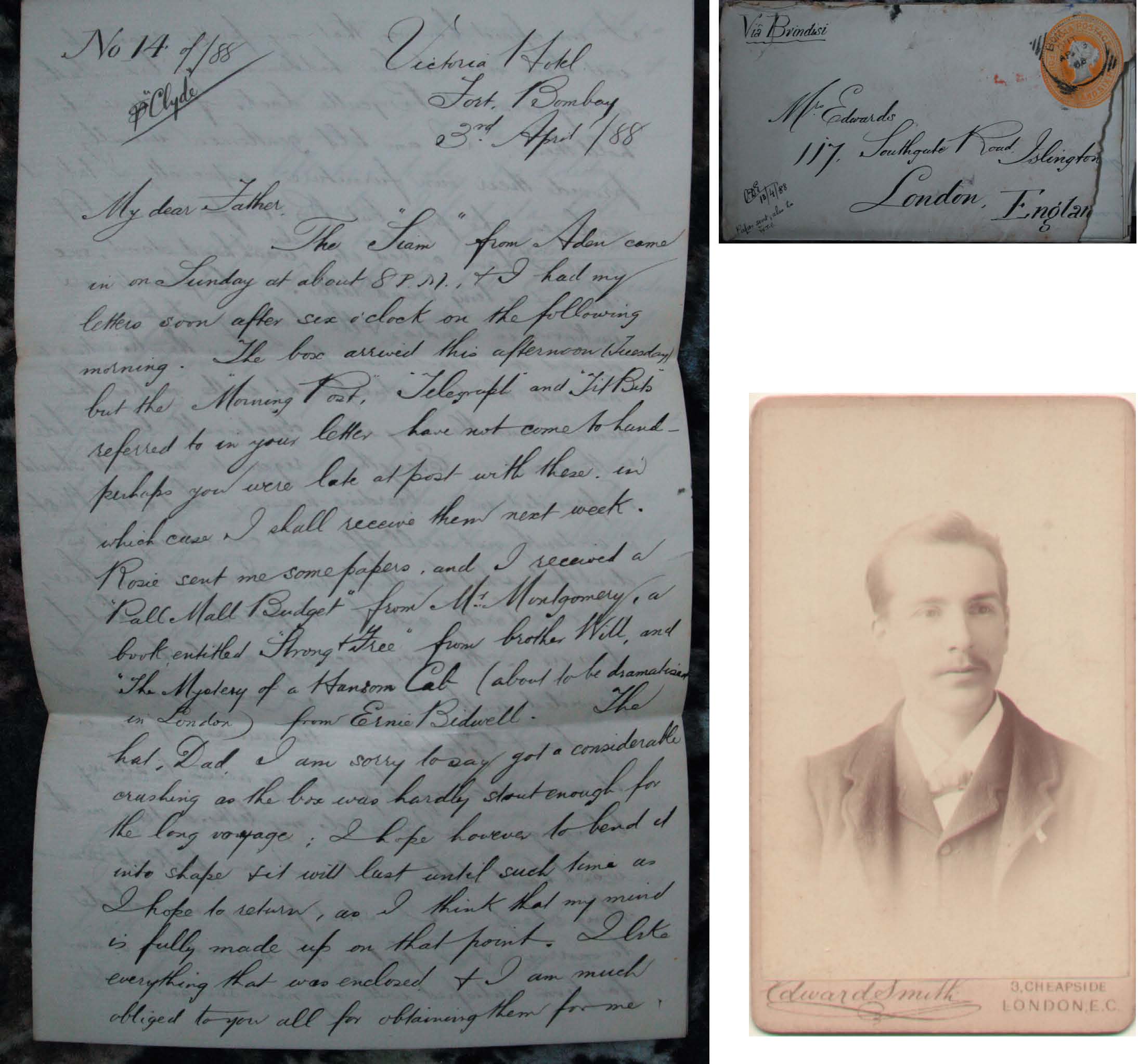

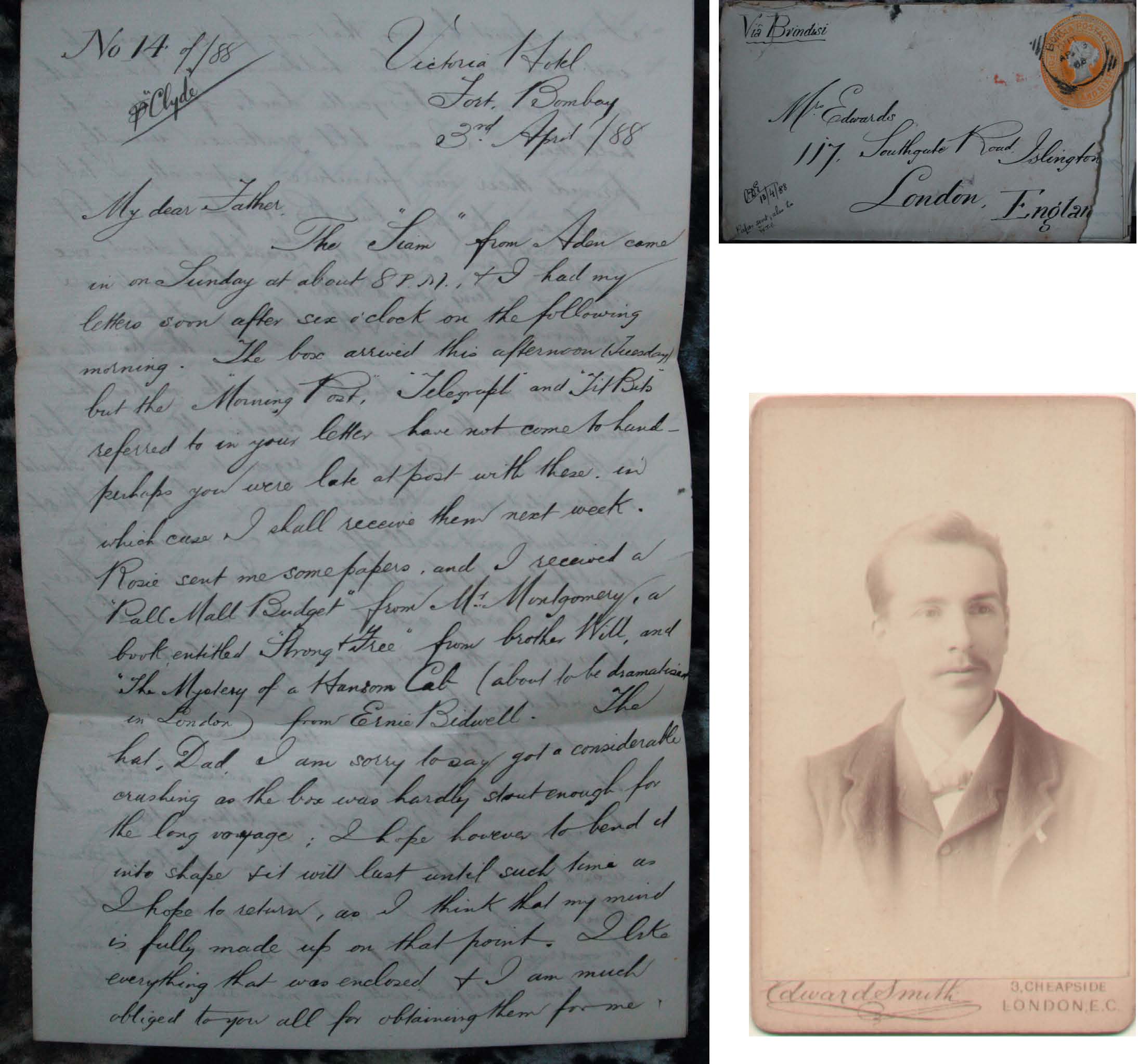

Victoria Hotel, Fort, Bombay

3rd April 1888

My dear Father,

The “Siam” from Aden came in on Sunday at about 8pm., and I had my letters soon after six o’clock on the following morning. The box arrived this afternoon (Tuesday but the “Morning Post” “Telegraph” and “Tit Bits” referred to in your letter have not come to hand – perhaps you were late in the post with these, in which case I shall receive them next week. Rosie sent me some papers and I received a “Pall Mall Budget” from Mr Montgomery, a book entitled “Strong and Free” from brother Will, and “The Mystery of a Hansom Cat” (about to be dramatised in London) from Ernie Bidwell. The hat, Dad, I am sorry to say, got a consid erable crushing as the box was hardly stout enough for the long voyage. I hope however to bend it into shape and it will last until such a time as I hope to return, as I think that my mind is fully made up on that point. I like everything that was enclosed, and I am much obliged to you all for obtaining them for me.

I am afraid however that my pretty ornaments will have now to lie hidden in my box, Father, as my room at Bycutta lacks furniture to hold them. I am told gentlemen usually provide their own furniture, especially I take it, gentlemen who pay but 80 rupees a month. Of course I have a bed etc., also a wash hand stand, one chair, and a tiny round table. Cupboards are unknown in India, and the hanging of pegs is objected to, and not unwisely. Even the knocking a nail into the bare white painted walls makes the cement crumble away, and an objectionable looking hole is the result. Everything requisite should no doubt be provided in a boarding house; but Mrs West is evidently not well off, and considering it is doubtful what length of time I shall remain there, I can hardly ask her to purchase a chest of drawers – this very necessary article she is not provided with, Dad. I must jog along with my box of Gladstone, the nuisance of this it necessitates my boy having access to all my belongings. I must do my letter writing on the wash hand table, unless I can pick up something cheap. I start my new abode tomorrow and I feel a bit worried as I am far from satisfied with my new servant. He will have charge of all my luggage, which is to go in a billock-cart in the afternoon, and he is stupid enough, I fancy, to make some absurd blunder in getting it to the bungalow. I should have left here today (a holiday)) but that between ourselves I find it a little difficult to meet my hotel bill. Our Administrative Officers looked forward so keenly to the Easter Vacation that the poor clerks were forgotten and have not yet received pagar / pay. Like any April fool I engaged my room as from the first, so that these few odd days mean that from 16 to 20 rupees out of my pocket. The hotel people will charge full price for the odd days. Mrs West’s bungalow is I think, the next but one to Pallongee’s Adelphi Hotel, where I could have got a complete suite of rooms for 100 rupees. By the way, it is reported that a doctor at this place died of Cholera a few days since, but I don’t fancy I shall be running into danger; the report has been contradicted. Indian people appear to have a great dread of this scourge, a nervous kind of horror, likely to spread an epidemic. I hope, Dad that I shall retain my health, and I am looking forward to spending next Christmas day at home. I shall want you to ask my sweetheart to stay in town for that day. I don’t think her Father would raise much objection under the circumstances, and she already anticipates it. Rosie says but little in reply to my decision, but I can see that she is very delighted. I am longing to see her and all at home. I write this under difficulties, a young mother with her two children and the screaming is simply too distracting. I was awake last night with the fretful cry of her baby at arms, which had evidently to be walked up and down, and I feel anything but fresh. It made me hope that Rosie and me can be free of family cares, for I suppose my luck will turn some day, and we will be able to marry. Gert’s wedding day tomorrow Father, and I am afraid poor Rosie thinking of the difference and the many miles between us will feel the ceremony acutely. She is I know very glad at Gert’s happiness and would be thoroughly happy too she says, if I were only with her at home. Unlucky beggar – am I not? Could I set up in trade? I have got through some of my packing, at which Rama is no earthly use, but I attended office too at my own free will today. We closed from Good Friday to Tuesday inclusive, but on each day, one European and about six natives attend. I was down for Saturday when I attended and on Monday Vining sent me a telegram as he was detained at home on urgent business. I stuck to work until a quarter to five in his stead. Garrett took his wife to Matheran. I must stop now Father until Thursday evening – no doubt I shall be too engaged in settling myself tomorrow night to think of much else. Drat that child – I am sorry though at leaving this hotel.

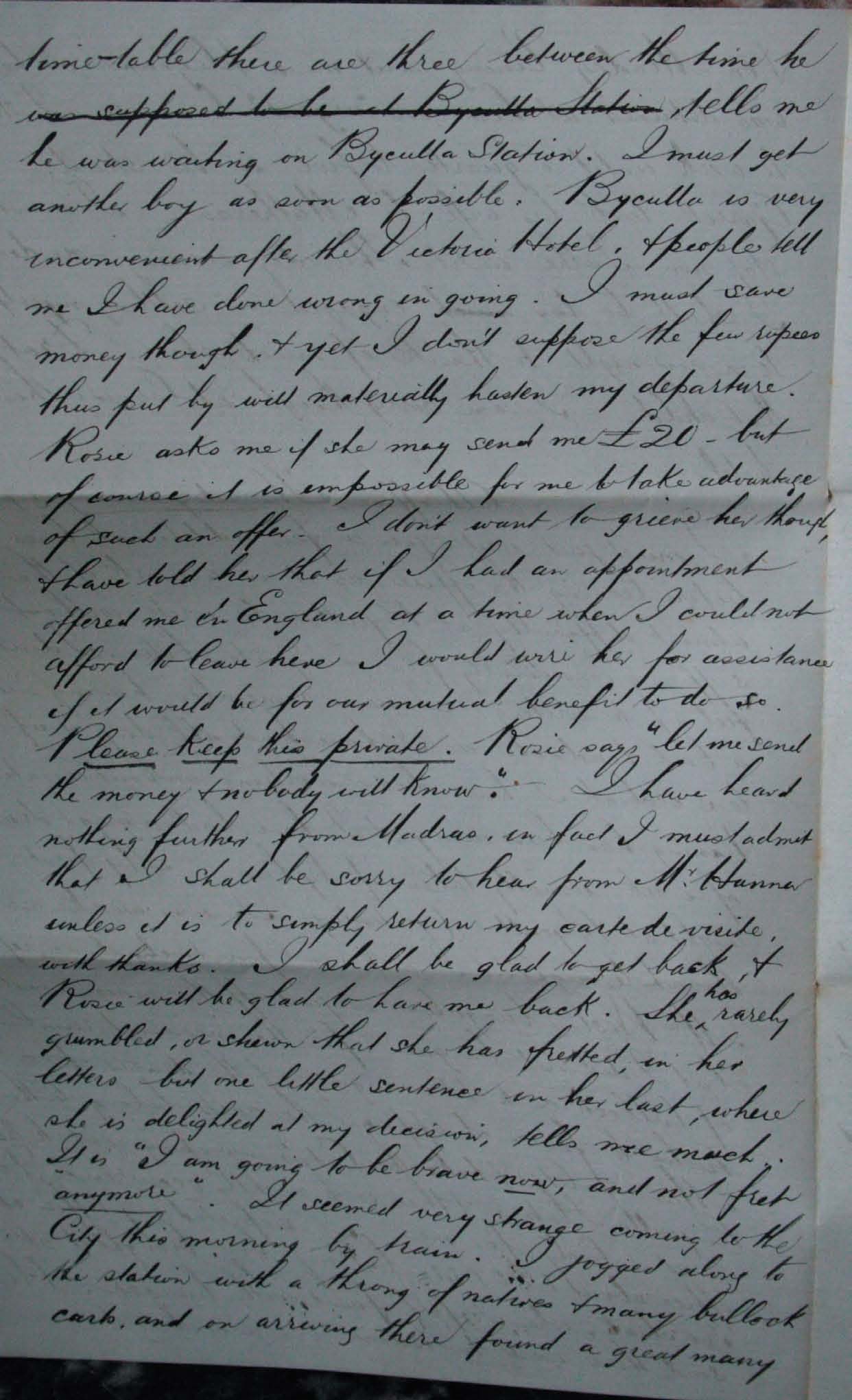

At office Thursday, 5pm., I must just write a few additional lines before leaving the office as it is a work of the utmost difficulty ay Bycutta to write without suffering considerably from mosquito bites. I don’t feel up to writing – I never remember having such a bad headache as I have had all day, and up to 5 o’clock I have been working without cessation. Vining has been away and I have had a great deal of work usually taken up by him. My first night at Bycutta (yesterday) I was awake nearly the whole night and I am now positively done up. Mrs West’s bungalow is just off the main road but I did not bargain for the incessant rumbling of bullock carts and the singing of the drivers from twelve to four – it appears the catrs belong to the municipality and take the city’s sweepings out to the Bycutta flats, and this is a nightly occurrence, Dad, so it is lively for me. I expect my Tiffin at office at 1.30PM., but my boy brought it at 3 o’clock, when I felt faint with hunger. He said there were no trains, but according to our time-table there are three between the time he tells me he was waiting on Bycutta station. I must get another boy as soon as possible. Bycutta is very inconvenient after the Victoria Hotel, and people tell me I have done wrong in going. I must save money though. And yet I don’t suppose the few rupees thus put by will hasten my departure. Rosie asks me if she may send me £20, but of course it is impossible for me to take advantage of such an offer. I don’t want to grieve her though, and have told her that if I had an appointment offered me in England at a time when I could not afford to leave here I would wire her for assistance if it would be to our mutual benefit to do so. Please keep this private. Rosie says “let me send the money and no-one will know”. I have heard nothing further from Madras, in fact I must admit that I shall be sorry to hear from Mr Hannah unless it is simply to return my carte-de-visite with thanks. I shall be glad to get back, and Rosie will be glad to have me back. She has rarely grumbled, or shewn that she has fretted, in her letters but one little sentence in her last, where she is delighted at my decision, tells me much. It is “I am going to be brave now, and not fret anymore. It seemed very strange coming to the city this morning by train. I jogged along to the station with a throng of natives, and many bullock carts and on arriving there, found a great many “City Clerks” waiting for their 10 o’clock train, it made me think of the mornings at home, but of course rather different to see all these men squatting cross legged on the wooden platform. They will sit like any Christian in office, but as soon as they are out and no bara sahib is watching, they squat, well why shouldn’t they, it is the custom of the country. Oh my poor head. If those carts keep me awake tonight, I shall think seriously of returning to the fort. At dinner last night at Bycutta I saw only one gentleman, but there were three old ladies, or rather, women of about 48 or 50 years of age. Indian life makes a woman look old before her time. The food is passable, but I missed the punkah terribly, as for every five mosquitoes in the fort, there must be fifty at Bycutta – it is not pleasant either, whilst at dinner, to feel the perspiration running down one’s face, but these old residents look as dry and as yellow as a well picked bone. I have never sat at dinner before without a punkah, except in Garrett’s tent. I had my breakfast quite alone this morning, and I must say I have made a better (breakfast) at the hotel. I am grumbling Father, but perhaps it is because I feel queer

– I have had several bad nights lately, and so you must put it down to that. You can sympathise with me. Time is flying, and I am afraid I shall miss the last train “home” that gets me in comfortably before dinner. After the 6.10 train there is no going to try another room on the opposite side of the house tonight, but it is one I cannot take, as Mrs West keeps it for a married couple that never arrive. I could get it for 100 rupees a month, but of course I might just as well be in the fort as pay that here. I am almost sorry I ever left, for it is very inconvenient in a number of ways. I must look out for another boy, as Rama is not only lazy but impertinent – he is an old fellow, and if I speak to him, he has a habit of mumbling half aloud as he goes away. I told him not to do this and he says “dusro naukar mito” – get another servant.

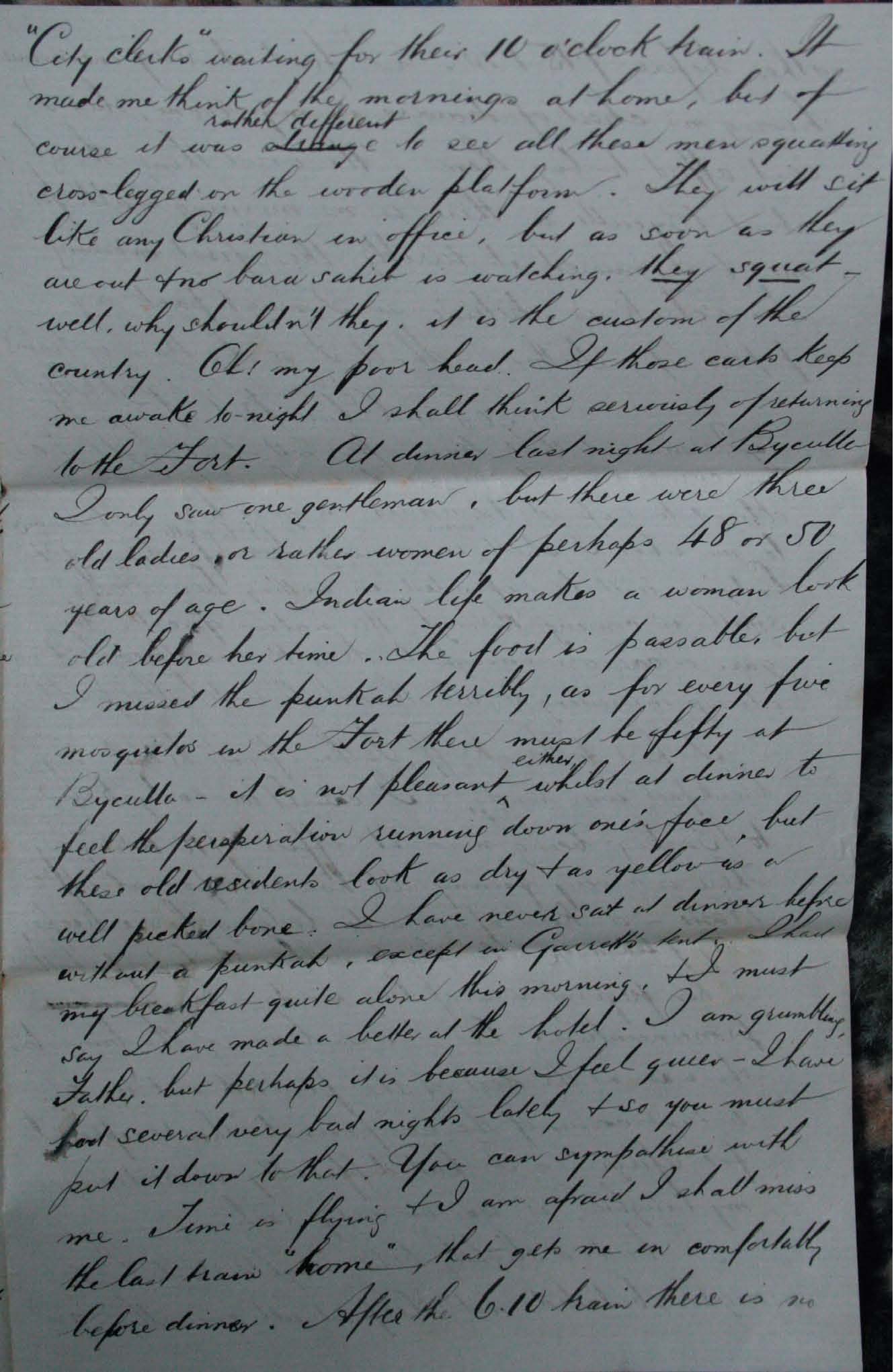

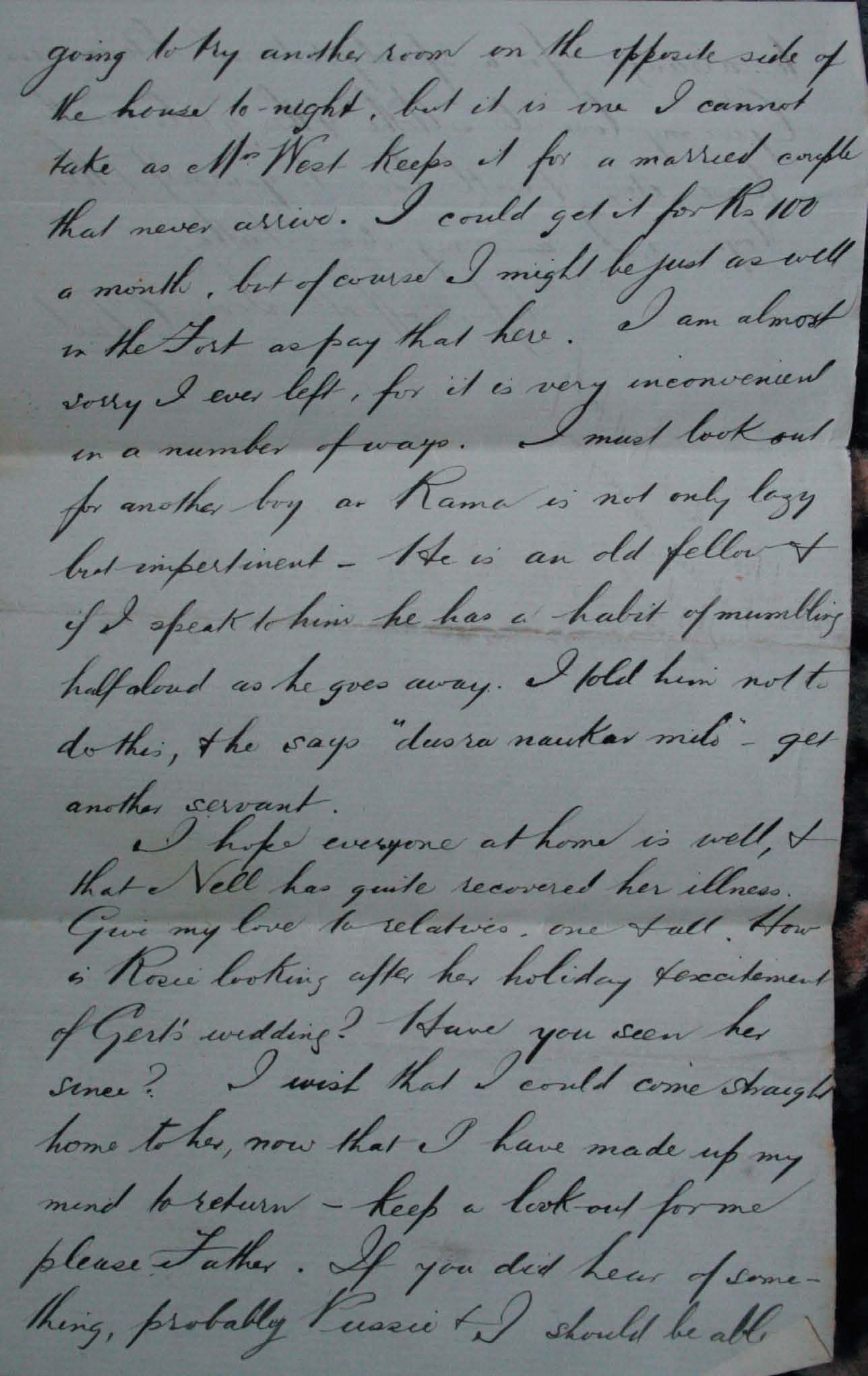

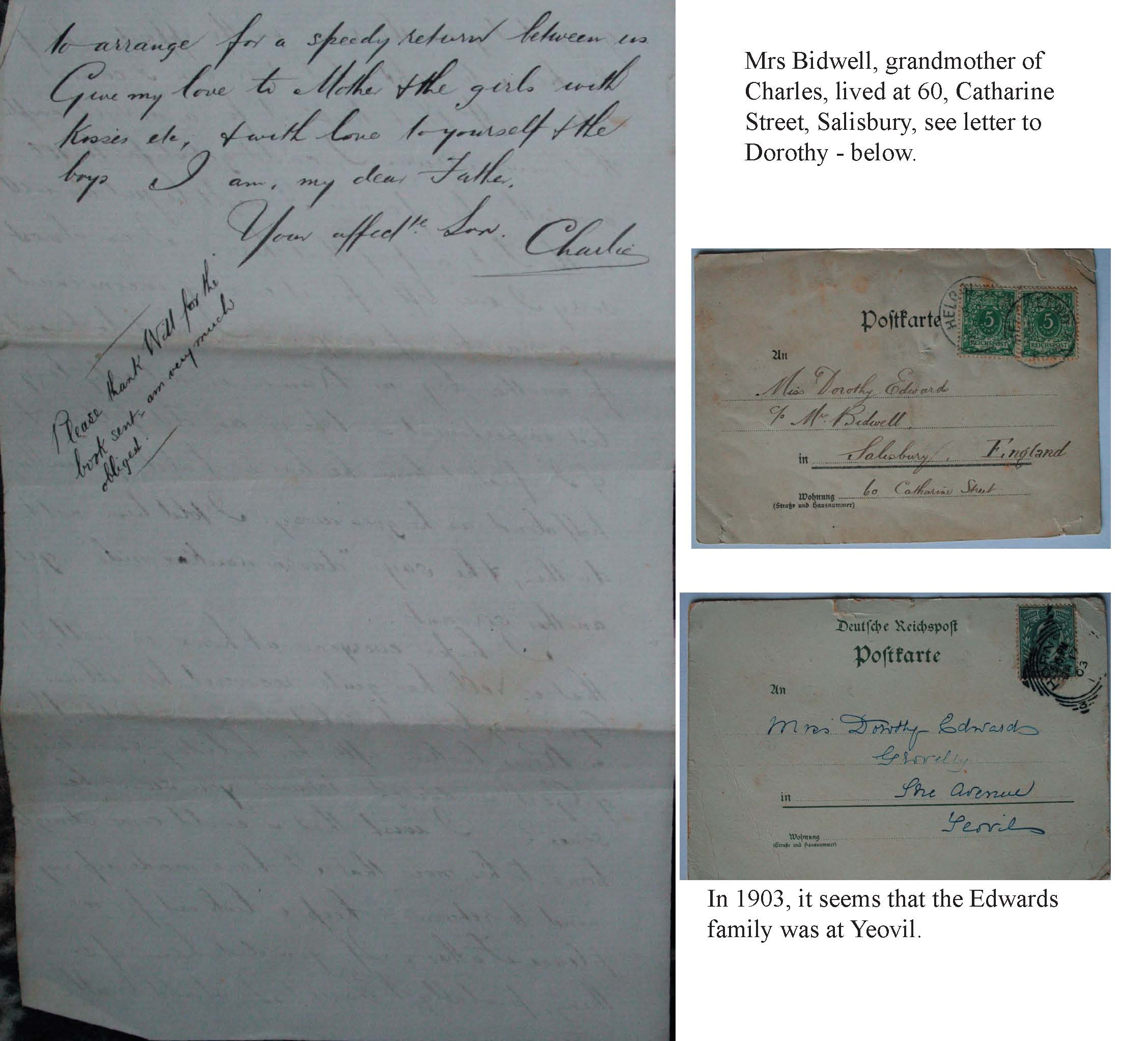

I hope that everyone at home is well and that Nell has quite recovered (from) her illness. Give my love to relatives, one and all. How is Rosie looking after her holiday and (the) excitement of Gert’s wedding. Have you seen her since? I wish that I could come straight home to her, now that I have made up my mind to return – keep a look out for me please, Father. If you did hear of something, probably Pussie and I should be able Mrs Bidwell, grandmother of Charles, lived at 60, Catharine Street, Salisbury, see letter to Dorothy - below.

to arrange for a speedy return between us. Give my love to Mother and the girls with kisses etc., and with love to yourself and the boys. I am, dear Father, your affectionate son, Charlie

Please thank Will for the book sent – am very much obliged.

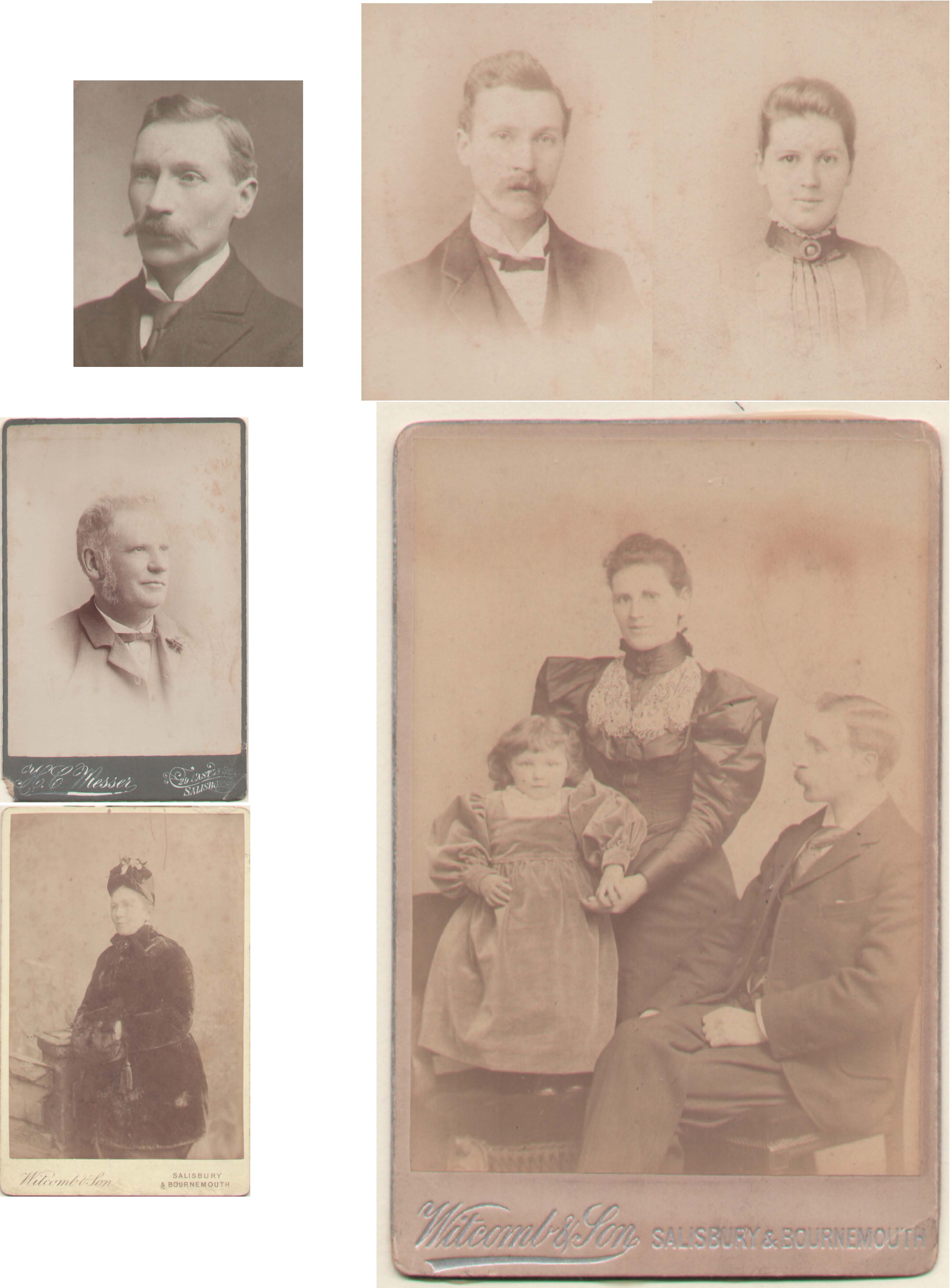

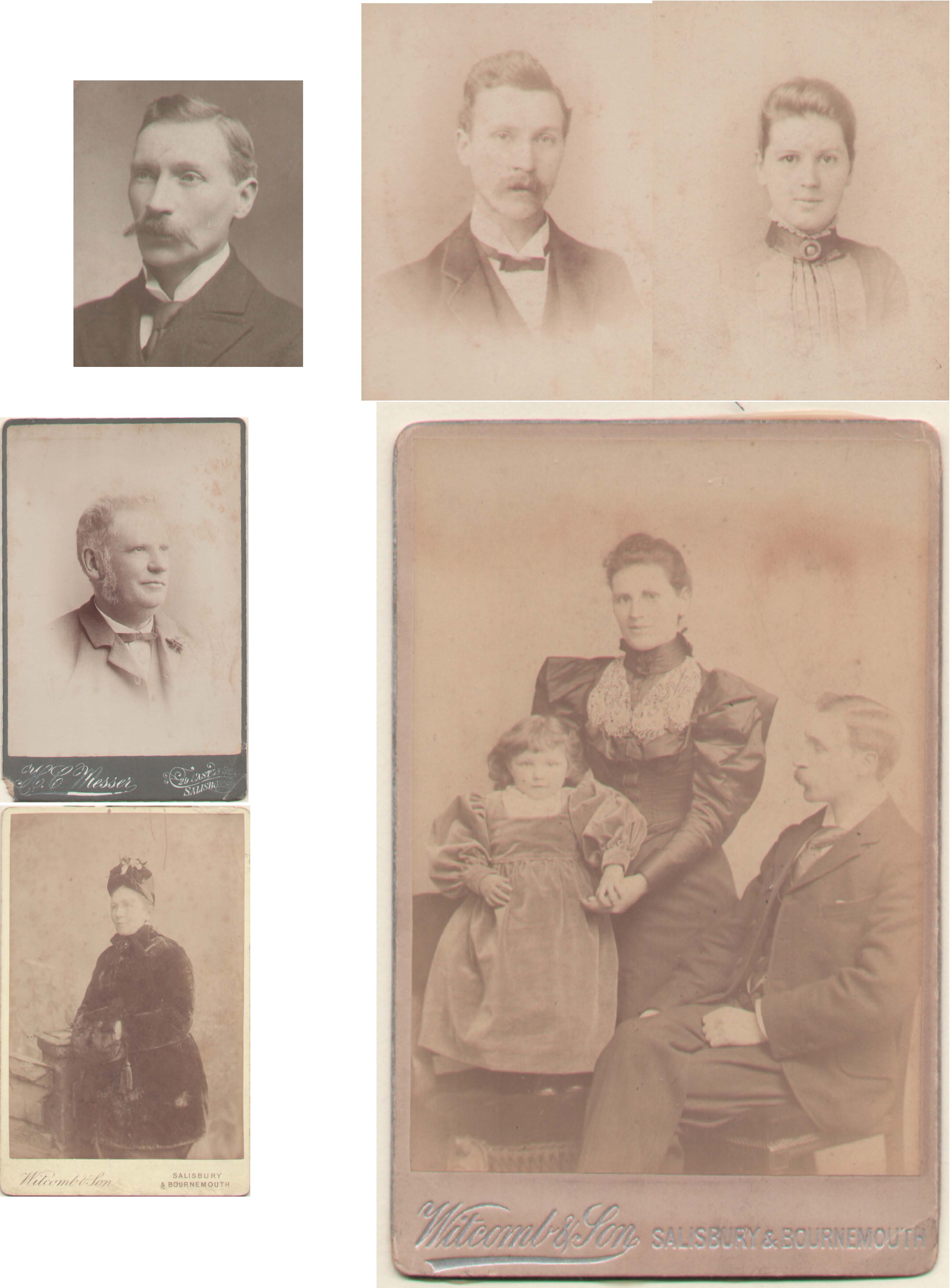

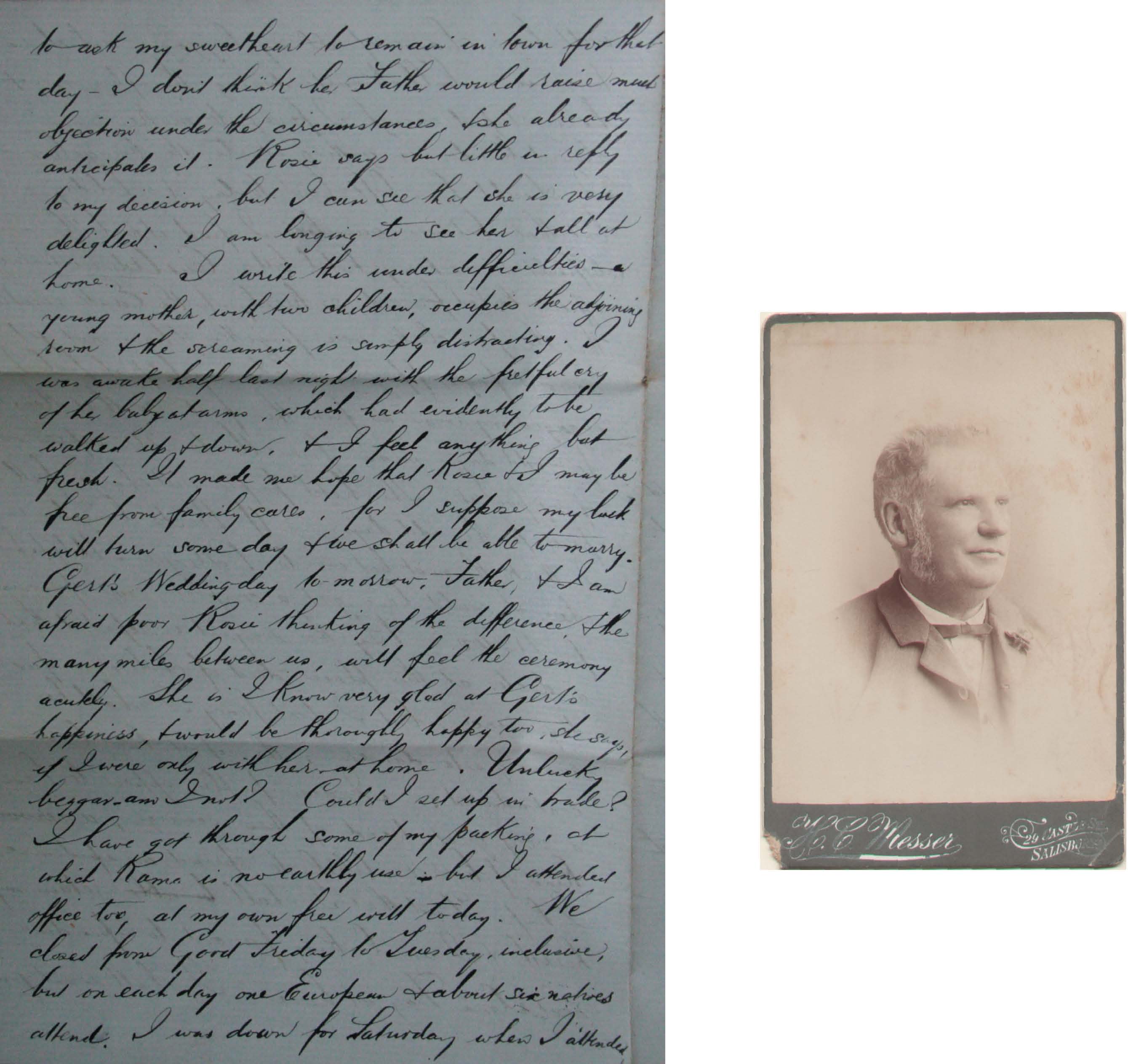

Wiiliam Edwards, Charles’ father, had married Charlotte Browne, and they had six children:

Elizabeth Annie, William Thomas, Charles Dorchester, Florence Mary, Alice Martha and Arthur John

Here is an abbreviated Family Tree

Relative Monarch

![]() Elizabeth

(1558-1603)

Elizabeth

(1558-1603)

![]()

![]() James

I (1603- 25)

James

I (1603- 25)

![]() Charles

I ((1625-49)

Charles

I ((1625-49)

![]() Charles

II (1660-85) James II (1685-88)

Charles

II (1660-85) James II (1685-88)

![]() William

III (1689-1702) Anne (1702-14)

William

III (1689-1702) Anne (1702-14)

![]() George

I (1714-27)

George

I (1714-27)

![]() George

II (1727-60)

George

II (1727-60)

![]() George

III (1760-1820) George IV (1820-1830)

George

III (1760-1820) George IV (1820-1830)

![]()

![]() William

IV (1830-37) Victoria (1830-1901)

William

IV (1830-37) Victoria (1830-1901)

![]() Edward

VII (1901-10) George V (1910-36)

Edward

VII (1901-10) George V (1910-36)

![]() Edward

VII ((1936-36) George VI (1936-1952)

Edward

VII ((1936-36) George VI (1936-1952)

![]() Elizabeth

(1952

Elizabeth

(1952

![]()

![]()

Christian b.21.5.1996 Morgan b 16.7.2004

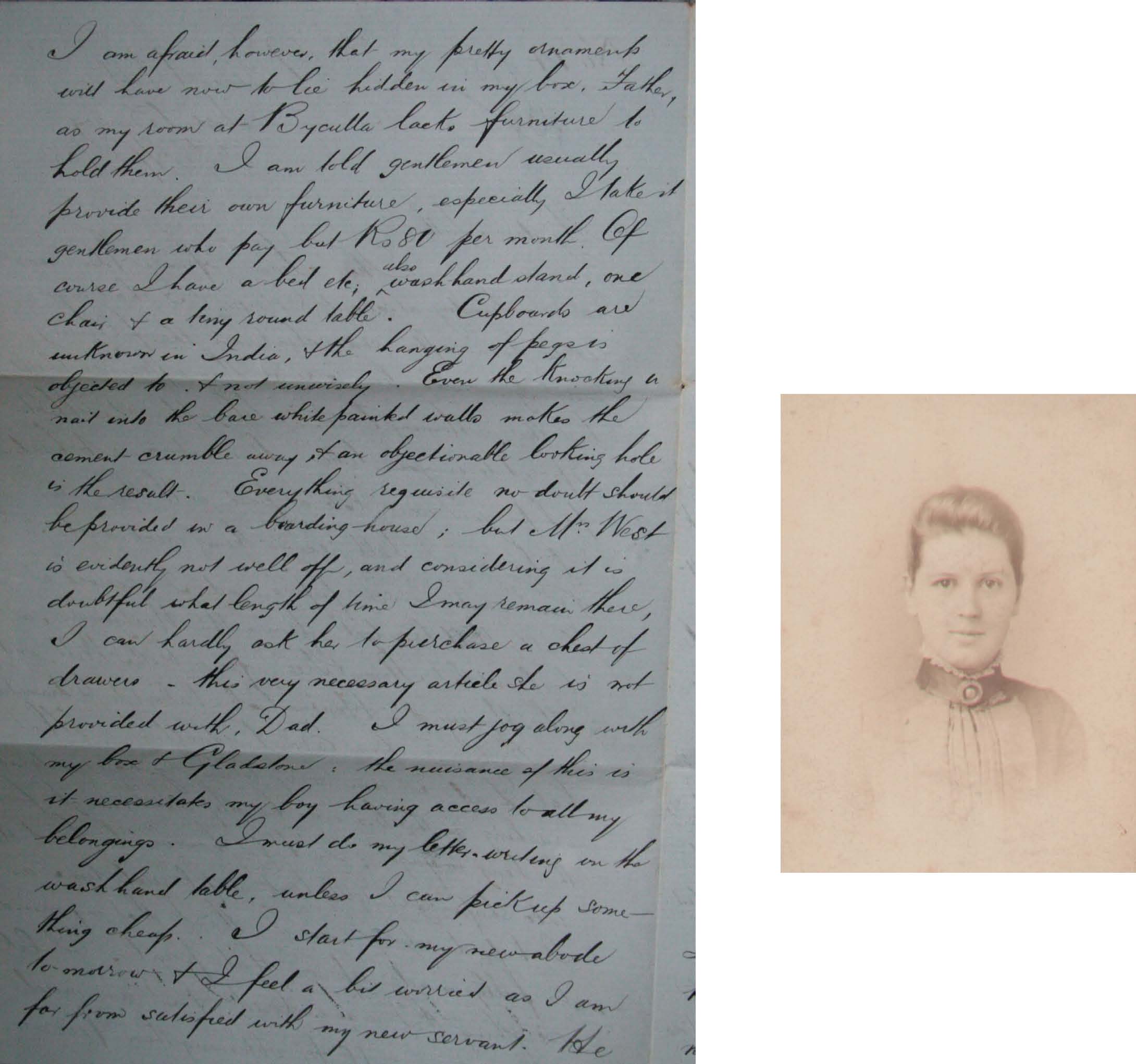

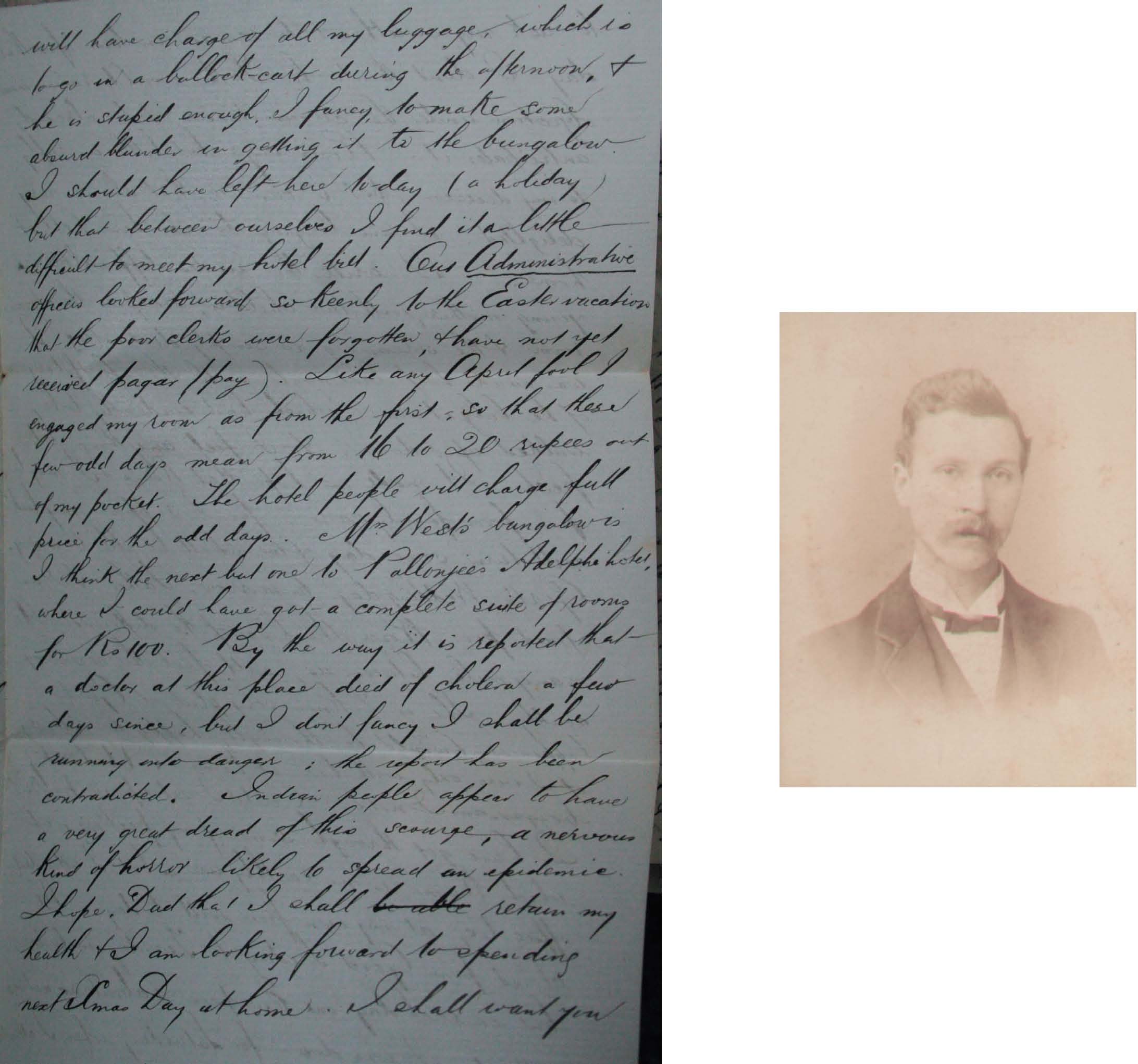

Charles Edwards aged about 45